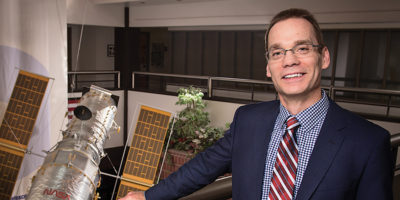

-Photography by David Colwell

You start January 5—what's your top priority?

My priority is the repeat violent offenders who are defining our city. We can't step foot outside the city of Baltimore without somebody saying, 'Oh is it really like The Wire?' It's so much more than that, but it's really hard to dispel that perception when we turn on the news and we open up the newspaper. First 100 days of my administration, I will sit down with the police department and develop a comprehensive process in which we're targeting these individuals. At the same time, barriers of distrust are what prevent jurors from actually convicting these individuals.

You've spent a lot of time with your transition team, which includes a lot of really big Baltimore figures—former mayor Kurt Schmoke, former congressman Kweisi Mfume—so what have you decided?

The idea was to pull in every facet, every sphere of influence throughout the city because everybody has a stake in the safety of our neighborhoods and communities. We meet on a weekly basis, and we're going through the current organization looking at the inefficiencies and trying to address organizationally, structurally, how we're going to change, what initiatives we're going to implement. I'm also traveling all across the country to different district attorneys' offices to see what best practices we can employ in Baltimore City. So I just left from the district attorney's office in Manhattan and the district attorney's office in Brooklyn. I visited the Fulton County district attorney in Atlanta, and today I'm actually traveling to California to speak with Kamala Harris, the attorney general of California and former San Francisco district attorney, and I'm also meeting with Jackie Lacey, who is the district attorney of Los Angeles. I'm going to meet also with Daniel Conley, who is in Boston. But I say all this because there are so many things that are happening all across the country that are really dynamic, and the purposes of that are to see, again, what best practices we can employ right here in our city.

So what are some of those best practices?

I talked about this throughout my campaign: There are barriers of distrust within the community and law enforcement, and we've got to find ways to bring down these barriers. It's never been more evident than now, right? It's the political climate all across the country. So what I've been doing, essentially, is seeing how other prosecutors are dealing with this distrust that is innate in Baltimore City. This is the home of witness intimidation where the "stop snitching" mentality began.

What I'm finding is that the community prosecution model, which is currently in place, is very different and looks very different all across the country. The community prosecution model is one in which you break down the prosecutors into geographic locations so that they can really get familiarized with the community and constituents and understand the issues within various communities. I don't want to go too far into specifics, but, for example, in Manhattan they have a criminal investigation unit where they're focusing more on the intelligence of prosecution, more or less collecting the information, interviewing, and going through the jail calls or collecting data on a lot of the individuals who are not only the violent repeat offenders but are also the individuals who are recidivists when it comes to quality-of-life crimes as well. So taking an approach where they gather the data and build a case against these individuals and then provide that information to the prosecutors, who would then go out and seek to get these individuals off our streets. So that's one approach.

Another program that I'm really interested in—and one of the reasons I'm going to California to speak with Kamala Harris—is a program she introduced called Back on Track. It's a first-time, non-violent felony offender program where you focus on these young folks. We know what happens when these individuals get these felony convictions: They can no longer apply for jobs, they can no longer apply for housing, and they can't really get any sort of financial aid, so what other alternative do they have than to go back out on the street doing what they were doing before? This program, it's more an intervention program in which you partner with the private business community, you partner with the union. These individuals go through a probationary period where they learn life skills, they learn job-training skills, they do community service, and at the end of their probationary period they're given a job—and not just, like, a fast-food restaurant, five-dollar-an-hour job, but a job with benefits that they can take care of their families. And at the completion of that, their felony record is wiped clean. Implementing those sorts of programs will allow us to utilize the courts—which in Baltimore City are inundated—for the real bad guys, the violent repeat offenders, the Nelson Cliffords, who is the five-time serial rapist breaking into people's homes and raping women by knife point who has gotten off four times in the last three years. Those are the sorts of initiatives that I want to be able to bring down those barriers of distrust.

When you say barriers of distrust prevent convictions, do you mean that African-American juries sympathize with defendants because they suspect police bias?

Essentially, yes. But I'm not going to say it's just based on racial lines. It's far more systemic than that. But I can say that there is a distrust for the criminal justice system, and sometimes rightfully so. They look at an individual and they will oftentimes look like their son, their nephew, their neighbor, and they're going to relate more to that individual than they do to you. As the administrator of the criminal justice system, it's incumbent on me to break down those barriers. That means I'm not going to come in and essentially fire community liaisons, which are the faces of the African-American community. That's what was done, so there has been an exacerbation of distrust because there's no longer any visibility and presence in various communities throughout Baltimore.

But isn't it unrealistic to think that one person is going to fix the entire system?

The fact of the matter is that I don't think that I'm going to go in and change the world, but I don't go into any sort of endeavor believing that I can't be successful. A lot of people told me that I couldn't run for state's attorney, that I couldn't run against an incumbent with powerful backers who outraised me four to one. They said that I was too young, too inexperienced. If I allowed that to define my purpose, I wouldn't be in the position that I'm in. I honestly believe that I'm following my passion, which has always been to reform the criminal justice system.

How do you feel about body cameras on police officers?

From a prosecutor's perspective, to have more evidence is better, right? It covers people on both ends. It covers the police department from fraudulent allegations, and it covers citizens because we now know the truth about what's happening. We can't allow individuals in the police to usurp their authority and to go above the people. They're in place to protect and serve, and if they abuse that authority what it does is it exacerbates the distrust within the criminal justice system and then we end up where we are today.

My grandfather was one of the founding members of the black police organization in Massachusetts. And my grandfather, my uncles, my mother, my father—I have five generations of police officers. I know that the majority of police officers are really hard-working officers who are risking their lives day in and day out, but those really bad ones who go rogue do a disservice to the officers who are risking their lives and taking time away from their families. You have to apply justice fairly and equally, with or without a badge, and that's what I intend to do.

Your husband, Nick Mosby, is on the City Council. How are you going to navigate the work-life balance so one, there's no appearance of conflict of interest, and two, you don't drive each other crazy?

There is no conflict of interest. I am beholden to the constituents who elected me. I'm not beholden to City Council, so there's never any conflict or should be any appearance of a conflict of interest between my husband being a public servant and myself being a public servant.

With regard to our marriage, I can tell you I just feel blessed. I have somebody who is also a public servant who understands that my heart and my passion is in serving people. And he's the same way. We both knew when we met at Tuskegee—we're college sweethearts—that we both had aspirations of being public servants and this is what our life and our passions has brought us. And I have to say that he's my rock. He's my foundation. We have two young children, but we have a balancing system. I don't know how we developed it! It's something that we do. We just do what we have to do and I wouldn't be able to get it done without him. We have a great support network of family and friends, but it would not happen without his support. So I'm just really grateful and have been truly blessed to have him as a spouse.

That's great. It sounds like a real partnership.

It definitely is. We alternate. Sometimes he'll take the girls to community meetings, sometimes I will. We have a lot of time away from home. It didn't really hit me until I was doing homework with my then-3-year-old during the campaign, and she looks up to me and she says, 'Mommy, when I grow up, I want to be a mommy state's attorney.'

Aww.

So I looked at her and I'm like, 'Okay, I know she knows what a state's attorney is because she hears it all the time with the election, but the fact that she said mommy first meant a lot to me because that means I'm doing something right. So they inspire me, and they inspire him, and that's what keeps us going.

That's nice that, in her mind, she knows that she doesn't have to choose one or the other.

Absolutely. And that's important because we have two girls. There's nothing that we can't do. That's the one thing I've realized during this process. I got to tell you that I was still working full-time as a civil litigation attorney, wife, mommy, candidate, fundraiser, but I realized that as women there's nothing that we can't do.

Well, jeez, all right then. If you could bottle some of that confidence and send it to me, that would be fantastic.

But that's all it takes though. To really believe in ourselves. Because, like I said, if I allowed naysayers to define my destiny, I would not be where I am. So it's just recognizing and saying, 'Hey, why can't we? Who am I not to do it? If not me, who? If not now, then when?' It's our time, and that's how I feel.