Paratrooper

Howard County’s Tatyana McFadden returns to her native Russia to compete in the Winter Paralympics.

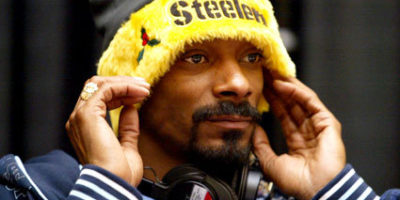

Tatyana McFadden trains for the Paralympics at a Columbia facility. -Photography by Sean Scheidt

"Ya sama!" As she walked around the orphanage on her hands, her arms acting as legs, the cheerful, bright-eyed, brown-haired little girl would repeat the Russian saying over and over. “Ya sama, ya sama," she'd proudly proclaim. “I can do it myself." That Tatyana McFadden is even alive is remarkable. Born in St. Petersburg, Russia, with her spinal cord outside her body, she was abandoned by her birth mother, essentially left to die. That she survived those critical first three weeks, when her spina bifida was ignored, then emerged from countless surgeries stronger; when she found a soulmate in the form of her adoptive mother, Deborah McFadden, who took her home to Clarksville, where she went on to achieve unprecedented athletic success—all of it could be called miraculous.

But nothing about McFadden's accomplishments—winning last year's Grand Slam (victories in the Boston, London, Chicago, and New York marathons, a feat never before done), the track world championships, and the Paralympic medals, which she hopes to add to next month in Sochi, Russia—is the result of some shadowy preordination.

McFadden has reached the pinnacle of wheelchair racing the same way almost all exceptional athletes achieve greatness: by expending sweat, maximizing her natural talent, and cashing in on a little bit of luck.

She possesses a rare combination of physical superiority and mental determination, traits she displayed at age five in that orphanage a world away.

“My past has a strong influence on where I am today," says McFadden, 24, who is paralyzed from the waist down. “Coming from nothing, I was able to survive. You have to work hard. There's nothing disabled about me. I live life just like everybody else. I drive a car. I love to go to the beach. I don't think people should be classified as disabled. You can always find ways to do things, even if you happen to be different."

Tatyana McFadden most certainly is different.

Throughout

McFadden's college years, which ended on December 20 when she delivered

a commencement speech at the University of Illinois, from which she

graduated with a degree in human development and family services, her

alarm would sound around 7 a.m. (an hour when many undergraduates are

just hitting the REM stage). She worked out six days a week, spending an

average of two to three hours training.

The results are striking. McFadden, who can bench-press 200 pounds (she weighs just 105), has a chiseled physique that can intimidate competitors on sight. Her biceps bulge; her cut shoulders show the effect of countless reps.

Yet her strongest attribute is her mind. She seemingly never tires, never allows the pushing and the pain to get the best of her.

“When I started racing, I wanted to prove something," she says. “I wanted to prove that with training, hard work, and dedication, you can be the best."

Her legendary vigor in the gym and on the track has earned her the nickname “The Beast." Coupled with her charming smile and warm, humble spirit, perhaps “Beauty and the Beast" is more appropriate. At the ESPYs, the ESPN awards show for which she's been nominated for honors multiple times, superstar athletes such as Adrian Peterson of the Minnesota Vikings flocked to be photographed with her.

It was at that event in Los Angeles that she introduced herself to a colleague of John Farra, high performance director of the U.S. Paralympics Nordic skiing team.

“She said, 'I want to be a Nordic skier,'" Farra says. “He joked with her and said, 'Nobody wants to be a Nordic skier, that sport's too tough.' She said, 'Well, you just don't know who I am then.' She is wonderfully stubborn, which all great athletes need to be."

After winning three track gold medals at the London Paralympics in 2012, McFadden abruptly announced that she was going to compete in an entirely new sport. And not just any sport, but the notoriously cold and taxing one of Nordic skiing. Later that year, McFadden, no fan of frigid weather, won a national cross-country skiing sprint title after only a few weeks of training.

“The biggest part of our sport that you can't fake is the fitness," Farra says. “That's a part that she clearly has. She has incredible physiological capacity and strength, but she needs to find ways to become more efficient with that energy she's spending. We think once it clicks, that's going to be a big factor in her climbing closer to the podium. She knows that she's not even close to maximizing her capacities in skiing."

Yet, in December, she placed 7th at the World Cup in Canada. The event was held in the middle of a dizzying few months for McFadden, who hopped from Illinois home to Maryland for three days around Christmas, then to Utah for the U.S. Championships, then to Europe for competitions before Sochi.

It's an exhausting lifestyle, but for a woman who as a girl feared she'd never go anywhere, there's no time to rest.

As

commissioner of disabilities at the Department of Health and Human

Services under President George H.W. Bush, Deborah McFadden traveled

extensively, evaluating organizations that might receive U.S. aid. It

was during one of those trips that she happened upon Tatyana at a dreary

orphanage with metal cribs, peeling lead paint, little food, and no

toys.

“She was crawling on the floor with a big bow in her hair and a sparkle in her eyes," Deborah says. “I had her sit on my lap, and she asked me in Russian about my camera. It's strange because I never had in my mind the thought of adopting, let alone a 6-year-old who is paralyzed from the waist down. I spent the day there and just had a great time. I went back to my hotel room that night and couldn't get her off my mind. It was something very strange."

A similar revelation was occurring that night at the orphanage.

“When my mom walked through that door, we had an instant connection," Tatyana says. “Something with my instincts went off, and I told everyone that she was going to be my mom. I really do believe in fate. It changed everything."

The adoption process took about a year. When Tatyana arrived in the U.S. with her new mom, she underwent a number of surgeries on her legs, which were atrophied behind her back. Doctors worried that Tatyana might not live a long life, so hoping to build her strength, Deborah enrolled her daughter in the Physically Challenged Sports Program at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore.

Run by Gerry Herman and his wife, Gwena, the program provides therapeutic sports and recreational programs for children with varying degrees of physical abilities. From the moment she first merrily splashed around in the swimming pool, it was clear Tatyana had found her niche.

“It was her genetics in terms of her physical attributes that set her apart right away," Gerry Herman says. “Taking up a new sport she may not have had the skills, but she was able to move faster than anybody else. She used to win swim meets just by moving her arms faster than everyone else, not necessarily because she was a good swimmer. She'd get to the end of the pool first—it wasn't pretty, but she was faster. It was basically just a matter of which sport she wanted to choose to be the best at."

McFadden competed in basketball, hockey, and swimming, but track was her favorite. The thrill of speeding in her wheelchair, nothing but the wind in front of her and competitors behind, couldn't be topped.

“I never wanted any help," she says. “I didn't want people picking up the ball for me, I wanted to bounce on the trampoline on my own. I was able to do that through sports. If I had never gotten involved in sports, I don't know where I would be today."

The 2004 Paralympics in Athens was McFadden's first foray into international competition. An inexperienced and nervous 15-year-old, she nonetheless won the silver medal in the 100 meters (and the bronze in the 200). The world's second-fastest woman in a wheelchair was not yet able to drive a car.

“Being on that stand with a silver medal, I knew I wanted to bring myself to another level," she says. “I knew this was something I wanted to do for the rest of my life."

McFadden has gone on to win eight more Paralympic medals, and her mother's house is jammed with trophies from her other triumphs. One that she does not have, however, is the gold medal from her victory at the 2010 New York City Marathon.

Soon after that win, Tatyana asked her mom to take her to Russia, back to the orphanage she still remembers quite well. To this day, the smell of cabbage, a frequent meal along with potatoes, conjures memories of her former home.

As the children at the orphanage gathered around her, she took out the medal and said, “This is very, very special. Few people have it. If you wear it, everyone knows you're the best of the best," her mother recalls. She then turned to the director, Natalia Vasilievma, the same woman who cared for her when no one could have possibility predicted this future, and gave her the gold.

“I can't think of anyone who deserves it any more than you, because you saved my life," Tatyana told her. “Someday I'll win another."

The next time she returns to her native land, McFadden plans on adding to her medal collection.

“I was born in Russia, so going back and competing in Sochi, it will have a special place in my heart," she says. “I'm an athlete. I'm there to represent America and do the best that I can."

In some ways the term “individual sports" contradicts itself. No one reaches the top without help from others, and the love of her mother, support of her sisters, camaraderie of friends and teammates, dedication of coaches, and divine hand of fate all aided McFadden in her momentous journey.

But when she's in her wheelchair crossing the finish line of a sprint or a marathon first, or in her ski sled propelling herself through the ice and snow faster than anyone else, she's there primarily because of her own desire, motivation, and drive.

She's done it herself.